The Russian invasion of Ukraine exposed Europe’s most severe and deep-rooted energy security vulnerabilities and exacerbated the energy crisis caused by gas supply deficits on global markets since 2021. The crisis revealed that most countries in SE Europe are particularly vulnerable to energy security risks

The Russian invasion of Ukraine exposed Europe’s most severe and deep-rooted energy security vulnerabilities and exacerbated the energy crisis caused by gas supply deficits on global markets since 2021. The crisis revealed that most countries in SE Europe are particularly vulnerable to energy security risks. The region’s historical lack of alternative energy sources to Russian oil and gas, the slow pace of the energy transition, and the more acute issue of energy poverty have all made the economic pain that resulted partially from joining the energy sanctions on Russia particularly unwelcome, both for policymakers and the general public. As a result, many SEE countries have been hesitant to follow the rest of Europe’s example, requesting derogation from common EU sanctions or even openly opposing measures to reduce the region’s dependence on Russia.

Natural gas use across the SEE region has been either stagnant or on the decline for most of the 2010s, due to a number of factors including improving energy efficiency, the switch to electricity (and even back to biomass in some countries), and limited competition due to incomplete gas market liberalization and integration. However, this trend has recently been changing, especially in Greece, where natural gas has been replacing coal in the power generation mix. With plans in place for boosting natural gas capacity across the whole region over this decade, dependence on gas could increase significantly.

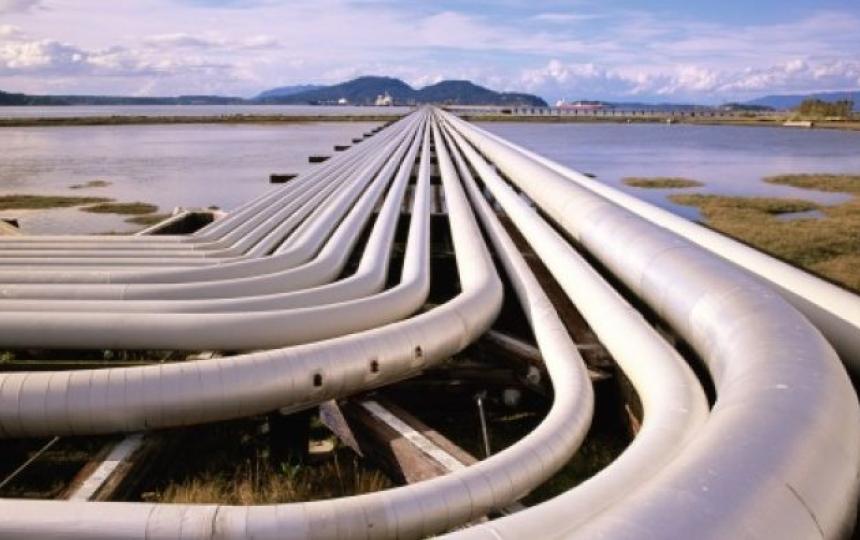

The main focus of the Monthly Analysis, which is available here, concerns latest gas infrastructure developments and consequent changes to gas supply flows, and an assessment of how flows might further change as planned infrastructure is built over the next few years. The central question is whether, as a result of these improvements, the SEE region can eventually enjoy a non-Russian gas supply future. The conclusion is that sufficient capacity is almost in place to import and distribute enough alternative volumes to replace Russian imports – assuming of course that this alternative supply is available and at a competitive price.

One of the main conclusions of the present analysis is that if the gas supply is there, SE Europe appears to be in a privileged position to replace its Russian volumes. However, in practical terms, a complete cut-off from Russian gas supplies is not yet possible, given Gazprom’s long-term contracts with Greece’s DEPA and Turkey’s BOTAS. Both companies are tied up with take-or-pay contracts with Russia. From a supply perspective, more LNG and a little more gas from the Southern Gas Corridor is expected by the end of 2024. Between 2025 and 2028, regional upstream comes into play, with Romania and Turkey as frontrunners. The Expanded South Corridor is of great importance to the region, providing real diversification, particularly if expanded in the future, this helping Western Balkan countries to diversify away from Russian gas as well as reduce their dependence on coal/lignite.