With Greece running desperately low on cash, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras was to meet on Tuesday with the head of the Russian energy giant Gazprom, amid speculation about a possible multibillion-dollar gas pipeline deal between Athens and Moscow.

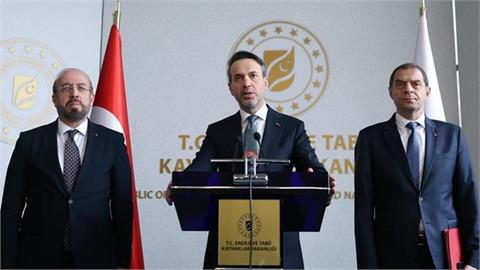

Mr. Tsipras, who has been negotiating for months with Greece’s international creditors drag on, was to meet with the Gazprom chief, Aleksei B. Miller, in the afternoon. An official close to the Greek prime minister played down the meeting, however, noting that no deal was expected on Tuesday. The office of the Greek energy minister, Panagiotis Lafazanis, with whom Mr. Miller was to meet separately, said simply that the two would discuss "matters of energy cooperation.”

But speculation about a potential pipeline deal continued to spread after Mr. Tsipras’s visit to Moscow this month. Discussions there included a possible discount on the price Greece pays to Gazprom for natural gas, and the possibility of a pipeline that would carry Russian gas to Europe through Turkey and Greece.

European antitrust regulators are expected on Wednesday to charge Gazprom with abusing its dominance in natural gas markets. The European Union depends on Russia for one-third of its natural gas, and Moscow and Gazprom have been developing plans for several years to build a new Western route under the Black Sea.President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia mentioned the possibility of piping natural gas to Europe via Turkey last year, after the European Union blocked plans for the so-called South Stream route, under the Black Sea and through Bulgaria. The prospect of antitrust charges against Gazprom raises questions about the likelihood of Mr. Putin’s new plan, which would require the participation of other European states.

Greece currently gets an estimated 60 percent of its gas from Russia, but it is a relatively small market. And even Turkey, the second-largest market for Russian gas in the region after Germany, would not consume and distribute all the gas Gazprom is developing, analysts say.

For a new pipeline to Turkey to make economic sense, the gas would need to transit through Greece to reach central and northern European markets. But the Gazprom plan could encounter some of the same resistance from the European Union that had led to the South Stream plans’ being scrapped last year.

"The problems they came across in Bulgaria are more or less the same questions they are going to come upon in Greece,” Trevor Sikorski, a gas analyst at the market research firm Energy Aspects, said about Gazprom. "As soon as they come into the E.U., they are going to have to comply with the regulatory arrangements of the E.U.”

Mr. Tsipras’s visit to Moscow this month riled European officials, who feared a Greek shift toward Moscow just as debt negotiations between Greece’s leftist government and its creditors were progressing slowly. Greece has refused to put in place further austerity measures, while its creditors insist that such overhauls are needed for them to provide the next installment of a bailout worth 240 billion euros, or about $258 billion.

Greek and German news outlets reported recently that Gazprom was considering providing up to €5 billion as an advance for the extension of the so-called Turkish Stream pipeline, but the news has not been confirmed by officials in Athens or Moscow.

A cash injection could hardly come at a better time for Greece, which is expected to run out of money within days unless it gets outside help, government officials have suggested. But it remains unclear whether Mr. Tsipras is prepared to take the political and geopolitical risks that could come with strengthening ties with Russia, potentially at the expense of the continued support of the eurozone and International Monetary Fund.

Reports that European regulators were planning to file charges against Gazprom — accusing the company of imposing higher prices on dependent markets in Southern and Eastern Europe — were seen by some Greek news outlets as reactions to the rumors of a Greek-Russian energy deal. The European Commission’s vice president for energy union, Maros Sefcovic, appeared to suggest as much on Monday when he said that all energy projects in the European Union must respect the bloc’s laws.

Even if Greece were to secure funding from Russia, the future of the pipeline would not be certain, and Athens needs money now. The desperate situation of Greece’s finances was highlighted on Monday when the government issued a decree forcing state bodies, with the exception of pension funds, to move their cash reserves to the central bank for the government’s use.

The move prompted an angry response from mayors and regional governors, who met on Tuesday to discuss potential responses, including possible legal action. The central government had already been dipping into the reserves of some entities, including a farmers’ fund, the Athens subway and the national employment agency, but it had always done so with their approval.

Greece’s dwindling financial reserves, and its debt talks with creditors, are expected to be on the agenda at a meeting in Riga, Latvia, on Friday of finance ministers from eurozone countries. Despite Greece’s looming cash crunch and fears about a possible Greek default and exit from the eurozone, European officials have said that they do not expect a decision on whether to unlock additional funding, as progress in negotiations has been minimal.

(New York Times)