The European Union has slammed the brakes on two big Russian pipeline projects to supply more natural gas to Europe, as part of its efforts to turn up the heat on Moscow over its incursion into Crimea.

The move will deal a blow to Russia's ambitions of increasing its gas exports and bypassing Ukraine as a transit country. It comes as the 28-country bloc is weighing other options to reduce its dependence on Russian natural gas, which accounts for over a third of EU supplies. Six EU countries, including Bulgaria and Lithuania, depend exclusively on Russia for natural gas.

The European Commission, the EU's executive arm, said this week that it would freeze high-level talks on South Stream, a pipeline that aims to carry up to 15% of Europe's annual gas demand via the Black Sea. It is due to be completed by 2018.The commission warned last year that the project couldn't proceed before it complied with EU legislation, including rules that limit pipeline ownership and require that other firms be permitted to distribute the gas, as well as environmental norms.

"I'm not accelerating our talks regarding pipelines such as South Stream. They will be delayed," Günther Oettinger, EU energy commissioner, told Germany's Die Welt newspaper this week.

A spokesman for South Stream, a joint venture between the Russian natural-gas-export monopoly OAO Gazprom OGZPY -0.27% and European companies including Italy's ENI SpA, said that as an infrastructure company, it didn't get involved in politics.

The commission this week also foiled plans by Gazprom to pump more gas through OPAL, a 290-milepipeline that transports Russian gas through Germany to the Czech border.

Gazprom had asked to be given exemptions from EU rules that prevent it from getting full access to OPAL, arguing the pipeline was underused. The commission was due to give its approval on Monday but said this decision was now on hold.

"We need more technical information," said a commission spokeswoman, without elaborating. Russian President

Vladimir Putin

said last month that the EU had agreed to give Gazprom full use of the OPAL pipeline.

Julian Wieczorkiewicz, an energy researcher at the Centre for European Policy Studies, a think tank in Brussels, said the twin moves were a political signal. "Clearly the commission is trying to punish Russia for what it has done in the Crimea," Mr. Wieczorkiewicz said.

The EU is currently drafting political sanctions against Moscow, such as visa bans and asset freezes on Russian individuals, which could be adopted next week after Sunday's vote in the Crimea on ceding with Ukraine to become part of Russia. The EU has said it considers the referendum to be illegal.

At the same time, officials in Brussels say they are eager to spur discussions on how the bloc could reduce its dependence on Russian gas. The current crisis has sparked fears of a repeat of 2009, when Russia cut off gas supplies to Ukraine amid a pricing and debt dispute, curbing flows to Europe.

Mr. Oettinger says Europe is now in a stronger position to withstand possible disruptions in supplies, thanks in part to a mild winter, more storage capacity and pipeline infrastructure that allows more gas to flow from west to east.

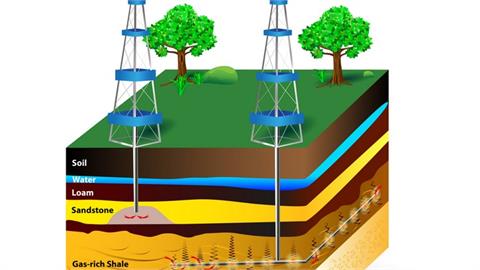

But he has also said that the EU should reach out to other gas exporters and build more terminals for liquefied natural gas, and that countries should also start exploratory work on shale gas.

"The Russians are now more dependent on our money than we are on their gas," said Mr. Wieczorkiewicz, adding that around half of Russia's revenues are derived from oil and gas sales. "The EU could also explore ties to Norway, Algeria and Qatar as alternative suppliers, increase the use of coal and import LNG."

But in the short term, others argue that the EU is short of options if it wants to use energy as a tool against Moscow. "Russia remains the largest exporter of gas to the EU; there's no way of [quickly] sourcing those amounts of gas elsewhere," said Simon Pirani of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

"Europe has to ask itself how important is the economic relationship with Russia, which provides that cheap energy, and how important is the political protest that it wants to make" about Crimea, he said.

(by Vanessa Mock, Wall Street Journal, March 12, 2014)