Climate change is one of the key problems of the modern civilization, one that the international community has been trying to resolve for several decades. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change defines the goal,

Author: Danijela Božanić, climate change expert

Climate change is one of the key problems of the modern civilization, one that the international community has been trying to resolve for several decades. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change defines the goal, while concrete actions to tackle climate change are laid down under the Kyoto Protocol (for 2008-2013), the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol (for 2013-2020), and the Paris Agreement (2021-2030).

The negotiations that led to the Paris Agreement lasted nearly a decade – the adoption of the agreement was deemed a major success of the French diplomacy and a significant step towards mitigating negative effects and consequences of climate change. However, success of the Paris Agreement comes down to the efficiency of implementing and achieving the targets under the agreement and the Convention. Achieving the targets requires joint rules, modalities, and procedures – which the Conference of the Parties (COP) and the Convention held in Katowice, Poland in early December sought to define.

Climate change and the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events (temperature highs and lows, precipitation, tornadoes, typhoons, snowfall etc.) seen in the past few decades are unquestionably the result of human activity. International bodies monitoring climate and studying causes and consequences of climate change (such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) taking into account natural causes have proven the impact of human activities on global warming and climate change.

Paris Agreement – a global political accord based on science

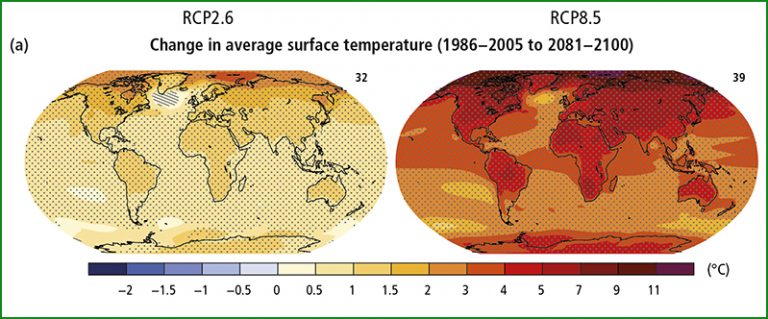

Global warming is a global problem and resolving it requires a global agreement on local (and national) action. The Paris Agreement within the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), adopted in 2015 at the Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC, is just that: a global political accord based on scientific results. The agreement sets the goal of limiting the increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, by taking action to reduce global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (starting from 2021) to net zero by the end of the century. Action and options for reducing emissions have been set voluntarily by states themselves, as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

Once the agreement is ratified, a NDC becomes a state’s obligation towards the international community. By ratifying the agreement, states took upon themselves to increase their ambition until and after 2020, as well as to ensure long-term and sustainable planning under low-carbon development strategies. Developed country Parties have also assumed the obligation to secure financial assistance for developing country Parties under the UNFCCC to achieve targets under the Paris Agreement in line with the Convention.

Emission cuts no longer concern only developed countries

It should be noted that the Paris Agreement makes no difference between developed and developing countries, except in terms of financing, based on their status under the Convention. Under the Agreement, all countries have emission reduction and adjustment commitments, as well as reporting obligations, which was not the case before. Therefore, apart from the fact that the Paris Agreement was adopted unanimously by 196 parties to the Convention, which is a rare case in the current political landscape, the fact that all ratifying countries assume commitments to cut GHG emissions and contribute to meeting goals under the Convention, in compliance with their ability, is also a new development (previously, under the Kyoto Protocol and the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol, only industrialized countries had these obligations).

Finally, by ratifying the Paris Agreement, countries confirmed the anthropogenic, i.e. human impact on climate, making it politically irresponsible and unacceptable for state officials to take positions to the contrary, even by insinuating climate change denial.

Great expectations from conference in Katowice

The agreement defined obligations, but not clear and precise rules, modalities, and pathways to achieve and track targets. Their adoption, i.e. the adoption of implementation guidelines for the Paris Agreement, was envisaged for 2018 by the agreement itself (under accompanying decisions of the COP). This raised the expectations from the COP in Katowice held in December 2018 to the level of expectations from the COP in Paris in 2015.

Not having implementation guidelines for the Paris Agreement is equal to not having the Paris Agreement at all, as its implementation would not be feasible without the guidelines.

The COP in Katowice was held in the year that followed the warmest year on record (since measurements began in 1880), in what confirmed the global warming trend given that 18 out of 19 warmest years were recorded after 2000. At the same time, extreme weather and other natural disasters caused about USD 320 billion in damage in 2017.

Bar raised on setting targets and reporting

Perhaps therein lie the reasons for adopting a package of guidelines for transparently tracking targets, as well as deadlines and new and more ambitious GHG emission reduction targets, which need to be submitted by 2020. The Paris Agreement also sets the 2020 deadline to submit long-term low-carbon development strategies.

Countries are also expected to establish their monitoring and reporting systems within the same timeframe. New emission reduction targets must contain information about:

benchmark values, including the benchmark year;

deadlines, including deadlines to achieve targets;

targets for sectors;

calculation assumptions and methodological approaches;

explanations of why the newly proposed targets are fair and ambitious and how they contribute to the ultimate goal of the Convention – the reduction of GHG emissions to the level that is not detrimental to life on Earth.

The package also includes recommendations and instructions for calculating GHG emission reduction targets. Decisions from Katowice also highlight the need to start work on determining the timeframe for the next commitment period (from 2030). The Katowice package highlights climate action links, including between action to achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and reduce disaster risk (the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030).

The Katowice package confirms the need to report on adaptation action as part of the global stocktakes under the Paris Agreement, the first of which is planned for the COP in 2023. The COP in Katowice resulted in defining adaptation reports, as part of national communications or national adaptation plans.

It was confirmed and recommended for adaptation to be included in NDCs. It was also recommended to monitor and report on adaptation at the national, regional, and local level to ensure a better understanding of progress achieved and further needs.

An inventory of internationally recognized methodologies for the assessment of adaptation needs should be produced by June 2020. Even though this deadline raises the issue of including adaptation in the first review of emission reduction targets, with 2020 set as the submission deadline, countries’ experiences so far seem to enable this.

Not having implementation guidelines for the Paris Agreement is equal to not having the Paris Agreement at all

The new obligation of biennial reporting on action transparency and producing annual inventories can be achieved through national communications and updated biennial reports. If not, the first ones need to be submitted by December 31, 2024, at the latest. Also, industrialized and other countries that have secured or plan to secure funds for developing countries are obliged to submit biennial information about implemented and planned budgets for climate change investments from 2020.

New actors in achieving Paris Agreement goals

In terms of the efficiency of achieving the Paris Agreement goals, increased efforts of local communities and other actors, especially the private sector, which have voluntarily set GHG emission reduction targets, are noteworthy. One of the reasons for this voluntary approach is quite certainly the fact that activities to cut emissions lead to an improved efficiency and application, if not development, of new technologies, which are increasingly significant for competing on the international market and further economic development. By the end of the COP, these obligations were assumed by over 9,000 cities from 128 countries that are home to 16% of the world’s population, as well as around 240 regions from 40 countries (17% of the global population) and over 6,000 companies from 12 countries.

The COP in Katowice for the first time featured an event aimed at presenting possibilities for achieving carbon neutrality in the tourism sector by 2050. The inclusion of tourism in the area of climate change is significant in view of the fact that the sector accounts for 10.4% of the world’s GDP and one in 10 jobs.

Two private sector initiatives were also presented – a fashion industry initiative to cut emissions by 30% by 2030 or a few years thereafter, compared to 2015, and the sports sector initiative, led by the International Olympic Committee, aimed at achieving carbon neutrality by sports organizations and at sports events.

Participation by the private sector, industry, local governments, and other actors in achieving the Paris Agreement goals is doubtlessly significant. Still, it is the national governments that have a key role in setting emission reduction targets and creating conditions for the targets to be achieved, as well as in reporting on progress to the international community.

Will the world be able to adapt?

The Paris Agreement secured solid grounds for reducing adverse effects of climate change and the Katowice package for its implementation. Most parties to the Convention (184 out of 196 countries) have also ratified the Paris Agreement, opting for low-carbon development. However, significant progress on establishing a monitoring and reporting system, as well as identifying and setting new emission reduction targets, is visible in only a few countries (the EU has established a monitoring and reporting system, and only 10 countries have submitted long-term strategies). There are certain initiatives for establishing monitoring and reporting systems, as well as for a review of emission reduction targets and producing long-term low-carbon development strategies.

However, it remains to be seen whether the review of the existing and preparation of new GHG emission reduction targets will take into account the fact that certain analyses have identified the need to phase out coal in OECD and EU countries by 2030, in China by 2040, and in the rest of the world by 2050, in order to achieve the Paris Agreement goals. It also remains to be seen by 2020 whether increased ambitions to reduce GHG emissions will be sufficient to ensure zero emissions globally by the end of this century, and thereby enable adaptation.

(balcangreenenergynews.com)